Nancy Lape Research

Nanocomposite Gas Separation Membranes

Project Background

To efficiently and effectively separate gas mixtures, membranes must exhibit both high gas permeability (fast transport) and high selectivity for one gas over the other. Unfortunately, these properties tend to be diametrically opposed: membranes made of rubbery polymers have high permeabilities but low selectivities, while membranes made of glassy polymers have high selectivities but low permeabilities. It has long been accepted that the addition of micron-sized inert impermeable particles to a polymer film decreases the permeability while leaving the selectivity unchanged. However, recent research has shown that adding nanoparticles to a special class of glassy polymers results in an increase in permeability, while retaining or possibly even improving the selectivity.

Our Work

We are examining the crossover between permeability enhancement and reduction with changes in particle size and polymer type. Understanding these effects will allow for the design of tunable membranes for gas separations.

- Experimental: We study gas permeation in a wide range of polymer types and nanoparticle sizes, and have developed a one-pot technique for creating well-dispersed nanocomposite membranes.

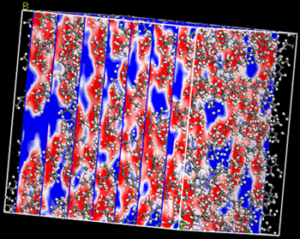

- Modeling: We develop molecular models (Materials Studio, Accelrys) to examine the molecular-level interaction between the polymer and nanoparticles.

- Characterization: We use Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to obtain images of our composite films. We also send samples to other labs for free volume determination via positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy (PALS) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) imaging.

Transdermal Transport

Project Background

Human skin provides a two-way barrier that prevents potentially harmful chemicals or diseases from entering the body while slowing water as it exits the body. These barrier effects are mainly due to the outer-most layer of skin, called the stratum corneum (SC). The SC is composed of many corneocyte (dead cell) “bricks” in a lipid bilayer continuum “mortar”; in order to reach the bloodstream, any molecule on the surface of the skin must pass through the SC.

- Mechanical Extension (Stretching): Studies on the mechanical behavior of skin have shown that lipids, the permeable domain in skin, should stretch significantly more than the (relatively impermeable) corneocytes when skin is stretched. We are investigating the potential increase in skin permeability.

- Hydration: Although levels of skin hydration can alter the transdermal transport of toxins and drugs by a factor of 6 or more, possibly by altering transport pathways, current methods for in vitro testing do not account for effects of variable skin hydration. We are investigating the effects of hydration on overall transport rate and transport pathways for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic (lipophilic) molecules via experiments and finite element simulations.

Our Work

- In Vitro Franz Cell Experiments: To test the permeability of skin in vitro at different hydration levels, we run permeation experiments on excised skin using Franz cells. Skin is placed between two chambers, one with a saturated drug solution and the other with no drug (water or buffer). Samples are collected at various time intervals and analyzed using HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatograph) or capillary electrophoresis (CE).

- In Vivo Tape-Stripping Experiments: To examine the effects of stretching on transport through skin, we conduct in vivo studies on human participants. Using a stretching apparatus designed by the research team, we apply either constant strain (fixed displacement) uniaxial extension or constant stress (fixed force) to the forearms of volunteers for the in vivo experiments. We place two drug-saturated patches on each volunteer’s forearm, one on the control (un-stretched) site and one on stretched skin. We then use a technique called tape stripping to remove several layers of the SC and analyze the results to compare transport across stretched vs. unstretched skin.

- Finite Element Modeling: We are using the finite element modeling (FEM) program COMSOL to run simulations of transport across the skin as the geometry (lipid and corneocyte dimensions) change with hydration or mechanical extension.