McFadden Shares in Coral Discovery

August 30, 2018

During her first-ever submersible dive on Aug. 23, coral reef expert and Harvey Mudd College biologist Catherine McFadden experienced a monumental moment. “We thought there might be some coral at the site, but I was expecting a fairly barren landscape of mud and rock with just some small, isolated coral colonies here and there.”

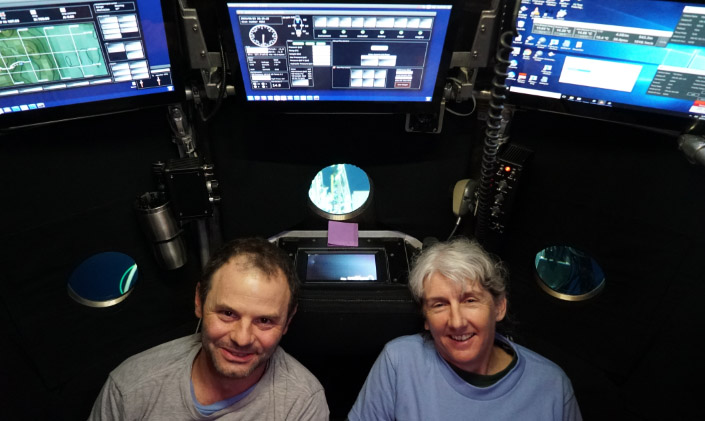

Instead, McFadden and the expedition’s chief scientist Erik Cordes “landed on a massive coral reef formed by a mix of dead coral rubble and large, dense stands of living coral,” she says.

The unprecedented find, approximately 160 miles off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, revealed extensive, previously unconfirmed reefs composed of the deep-sea stony coral, Lophelia pertusa. Researchers are using the deep-sea submersible Alvin to visit previously unexplored locations, including canyons, gas seeps and coral ecosystems, in order to identify and ultimately protect sensitive habitats.

During nearly eight hours in the submersible, McFadden, Cordes and pilot Bruce Strickrott viewed and sampled different coral species, including Enallopsammia, Madrepora, and octocorals (plexaurids, primnoids, Anthomastus). Lophelia was by far the most sampled coral.

The Deep Search team estimates that there are approximately 85 linear miles of discontinuous Lophelia reef off the U.S. East Coast. As the Lophelia grows and dies over many hundreds of years, new Lophelia grows atop the old skeletons, forming 80- to 100-meter high mound structures that stretch further than scientists had imagined.

“It was really exciting to see so much coral (and no mud!),” says McFadden, the Vivian and D. Kenneth Baker Professor of Biology at Harvey Mudd College. “But the magnitude of the find didn’t really sink in until several hours into the dive when we realized we were still traveling over coral. In the course of six hours, we moved about 1.5 km and never left this reef.”

“While Lophelia reefs are known to occur off the coasts of Florida to North Carolina at depths averaging 350-600 meters, the presence of these reefs at deeper depths (greater than 700 meters) and farther offshore make these newly discovered reefs unique, potentially connecting deep-sea coral habitats from the south to the north,” says biologist and NOAA web coordinator Caitlin Adams in a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration news release. “Connected reefs can be more resilient to environmental change, thus this extensive reef complex might help to improve the overall health of deep-sea corals off the East Coast and in the larger Atlantic ecosystem.”

McFadden’s research focuses on the systematics and taxonomy of octocorals. For two weeks in August as a member of the Deep Search science team aboard R/V Atlantis, a 274-foot research vessel owned by the U.S. Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, McFadden collected and preserved octocorals, mussels and their associated species for molecular systematic and population genetic studies.

“It’s pretty mind-blowing to know that the existence of this huge biological structure was completely unknown until now and to have been one of the first humans to visit it,” says McFadden of the Lophelia reef discovery.

With funding from the National Science Foundation, McFadden’s research group at Harvey Mudd College is developing next-generation sequencing-based target-enrichment methods to study phylogenetic relationships and skeletal evolution in anthozoan cnidarians (corals and sea anemones). McFadden is particularly interested in understanding species boundaries and the generation of biodiversity in shallow-water soft corals, and in recent years has focused on the coral reef communities of the South China Sea.